Andy Murray training with Nishikori in Miami earlier this year. Source: NHK.

In a recent documentary on NHK it was revealed that a new level of espionage was creeping into men’s professional tennis. It was reported that Andy Murray approached Hawk-Eye to track his practice session with Kei Nishikori at Miami earlier this year. It was also revealed that Murray was now a regular customer of Hawk-Eye and is using the data to seek new insights into his game, and his opponents.

In recent years there have been a number of high profile spying events in sport that have made headlines. In 2007 the New England Patriots were caught filming the New York Jets defensive coaches’ signals during a game. In 2014 the French National Football (soccer) team sighted a drone over one if its practice sessions prior to the 2014 world cup and in the same year Australian Rules Football club Port Power ejected an opposing spy from one of their training sessions.

Spying on rival players in tennis is not new. Tennis coaches have long sat courtside at practice sessions to try and catch a glimpse of their next opponent or an up and coming player making headlines in the junior ranks. Coaches and players regularly use video to scout opponents technique, tactics and fitness. But Murray’s request for Hawk-Eye to secretly track a training session is perhaps a whole new level of spying that we have not seen in tennis before. Did Murray crossed the line? Are there even rules in place to prevent this?

Players can request match data from Hawk-Eye at any time. Few do, but the option is available for them and this is within the rules. What’s interesting is that this is the first time we have heard players requesting that the Hawk-Eye system be turned on to secretly track the ball and player movement in a training session. From what we understand Nishikori had no knowledge about Murray’s request.

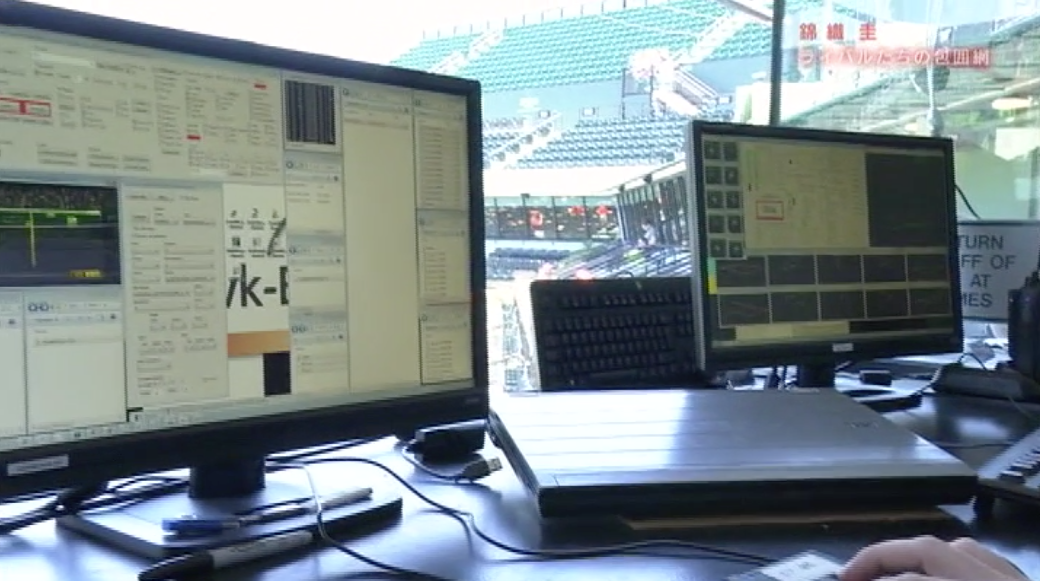

Inside the Hawk-Eye bunker in Miami during Murray’s training session with Nishikori.

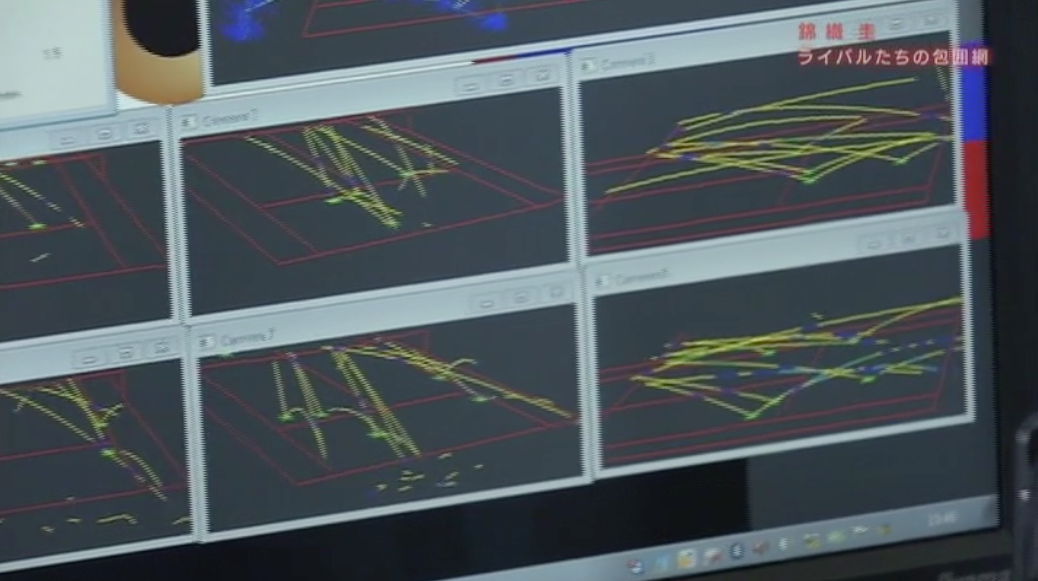

The richness of the Hawk-Eye dataset cannot be underplayed, evidence of this was on display during the NHK documentary. One of the huge advantages to players is that when they make a request for the data they are supplied with both their data and their opponents data. So not only can the player answer questions about their own game but they get valuable insights into their opponents too. It does however raise the question about what benefit a single training session would provide to Murray. From my experience a single match, and in this case a single training session only provides a limited insight into a players patterns and tendencies. Studying trends and patterns over time is where the real value lies.

The output from Hawk-Eye during the Murray Nishikori training session.

Murray is no stranger to technology. He recently joined the board of Seedrs Advisory where he gives business advice in the areas of health, sport and wearable technology. His growing interest in UK tech starts ups shows he has a genuine interest in this area, and he seems keen to use the latest technology to his advantage on and off the court.

Other sports like the NBA, EPL and NHL are caught up in an analytics storm at the moment. Tennis has traditionally been left in the dark ages with respect to analytics but perhaps Murray’s actions are confirmation that the game is changing. Tennis players and coaches are becoming more intrigued by analytics, and the data that is being collected on them. Murray is now a regular user of Hawk-Eye data, but it seems he is keen to take advantage of the system one step further. Perhaps Murray was simply being curious? Or perhaps he and Amélie Mauresmo had genuinely planned to gain insights from the training data. Players are starting to ask the right questions, and some of them are clearly pushing forward with their own independent analytics and detective work. I say fair play to Andy Murray for pushing the boundaries, and seeking an edge wherever he can. Tennis may be on the edge of a new frontier in analytics after-all.